The Isle of Skye lies close to the northwest coast of the Scottish Highlands and it Scotland’s largest tourist destination after Edinburgh. Rightfully so, as it contains what are thought to be the only true mountains in Britain – the dramatic Cuillin and Red Hills. The Cuillin, also known as the Black Cuillin, is a rugged ridge of peaks that are the remains of a volcano. The Red Hills are the adjacent landforms to the Black Cuillin, having a very different mineralogy and much gentler slopes than their Cuillin neighbours. These mountains have been a mecca for experienced climbers, scramblers and even hillwalkers for over 150 years. They offer breathtaking views of the ancient volcanoes that once erupted on Skye and also a range of satisfying ascents. Rising straight from the sea with little vegetation, these mountains first appear precipitous, but if you get close enough you see the enchanting scenery that the cloudy peaks offer. J. A Macculoch, a Scottish writer, put this beauty into words on his first visit to the mountains: “Here and there a black precipitous scour looms out of the hillside, but the hills themselves in their white dresses are folded softly against the sky, and the snowy peaks of the Cuillin shimmer away like some ethereal fantasy into the sapphire heaven. Were it not for the shadows cast of the hills by their outstanding rocks and bluffs, they might be fleecy clouds, forming and dispersing and reforming in dreamy air.”

After the three ancient continents collided to form what we now know as the United Kingdom, the Earths crust began stretching apart and forming the Atlantic Ocean. During this stretching, the mantle began to melt an magma welled up beneath the crust forming ‘hot spots.’ Around 61-55 million years ago, deep fractures in the crust allowed the magma rise and erupt at the surface. The lava flows from these eruptions built up vast plateaus in the Inner Hebrides but can also be found on the islands of Mull, Iona and Staffa. The hexagonal columns were formed when the lava cooled and shrank as it solidified, jointing and cracking into these distinct shapes. This hexagonal jointing is an entirely natural phenomenon and can be seen when mud dries out; since the lava contracts inwards as it cools, the polygonal jointing is essentially the most ‘economical’ shape for the rock to attain.

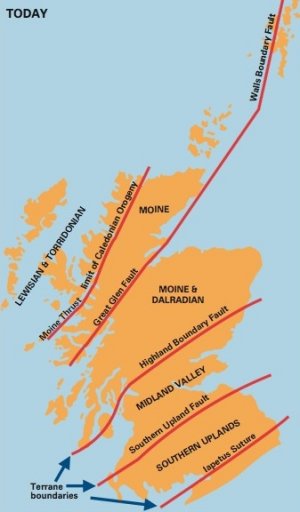

The geology behind this area is even more diverse, as the boundaries of the park envelop the Highland Boundary Fault – one of the four faults upon which Scotland was pieced together. This fault is significant as it geologically separates the Highlands from the Lowlands but distinct changes can also be seen in the weather, vegetation, wildlife and landuse. The boundary fault cuts rights through the centre of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, making them places of geological wonder and breathtaking views of landscapes so different from one another.

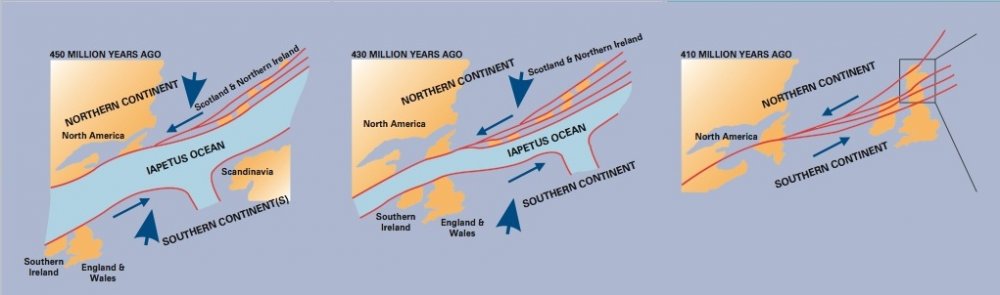

This mountain building event was known as the Caledonian orogeny. The newly united continent drifted across the planet, spending time in almost all Earth’s climatic zones including equatorial and desert, and eventually where it exists in present day. Beginning around 60 million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean formed from a thinning and diverging in the Earths crust, and Scotland drifted away from the rest of Laurentia. This stretching allowed molten rock to emerge at the surface that created a chain of volcanoes running along the west of Scotland. From this point until present day there were numerous periods of glaciation coupled with massive amounts of erosion to shape the landscape of Scotland we see today.

Whaur the sun shines bright on loch lomond

whaur me an' my true love wiLL ne'er meet again

on the bonnie, bonnie banks o' loch lomond"

Back Next

Magazine Posts

Magazine Posts Table of Contents

Table of Contents