Post title...

Post title...

Post title...

Post title...

Post title...

Posted

|

Views: 1,166

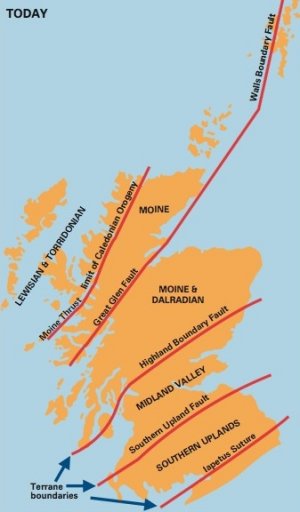

The geology behind this area is even more diverse, as the boundaries of the park envelop the Highland Boundary Fault – one of the four faults upon which Scotland was pieced together. This fault is significant as it geologically separates the Highlands from the Lowlands but distinct changes can also be seen in the weather, vegetation, wildlife and landuse. The boundary fault cuts rights through the centre of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, making them places of geological wonder and breathtaking views of landscapes so different from one another.

The Highland Boundary Fault marks the major change from hard Dalradian

metamorphic rock in the Highlands and softer Devonian sandstones in the

Lowlands. These two disparate crustal blocks were brought together between 450

and 420 million years

ago. The area above the fault is known as the Moine and

Dalradian terrane, and below the fault is the Midland Valley.

The hard Dalradian rocks were originally marine sands, muds, lime-rich

deposits and volcanic ash that were buried and altered by heat and pressure

during the Caledonian orogeny to become metamorphosed. New minerals were

formed: the sands and muds became slates, phyllites and schists. The softer

Midland Valley rocks were deposited in layers in ancient freshwater lakes,

which became compressed and hardened into red sandstones, pebbles and

conglomerates. Situated between these two terranes is the Highland Border

Complex, which contains rocks different than both the Highlands and Lowlands.

The Complex contains a sequence of lavas, conglomerates, limestones black

mudstones and sandstones that originated from the floor of an old ocean basin.

The actual Highland Boundary Fault line is marked by an intrusion of serpentine,

a base-rich mineral derived from great depths in the Earths crust.

Loch Lomond is the result of the erosive power of glaciers, which

scoured the Loch into the face of the Earth. The current location of the Loch

was the main corridor for ice movement originating from the north. Loch Lomond

is tadpole shaped; the north is narrow and deep where the glacier eroded more and

the south is wide and shallow where till and sediments were deposited (below).

The most interesting result that this geology has had on the landscape

is the sharp change from Highlands to Lowlands, which can be seen from the

summit of many hills in the national park and also in Loch Lomond. The stretch of islands from Conic Hill, Inchmurrin,

Creinch and Inchcailloch are all part of the Highland Boundary Fault and make a

distinct line through the Loch. The national park offers many hillwalks but the most popular is Conic Hill as it provides the best vantage point of this geological phenomena. A popular scenic tourist trail, the West

Magazine Posts

Magazine Posts Table of Contents

Table of Contents