Ryan's Post :):):):):)

Ryan's Post :):):):):)

Alec's Post

Alec's Post

arielle's post

The current food crisis in East Africa has left millions unemployed, homeless, starved, and dehydrated— the worst drought to hit East Africa in 60 years.[1] But what caused such a massive crisis, and who is paying the biggest price?

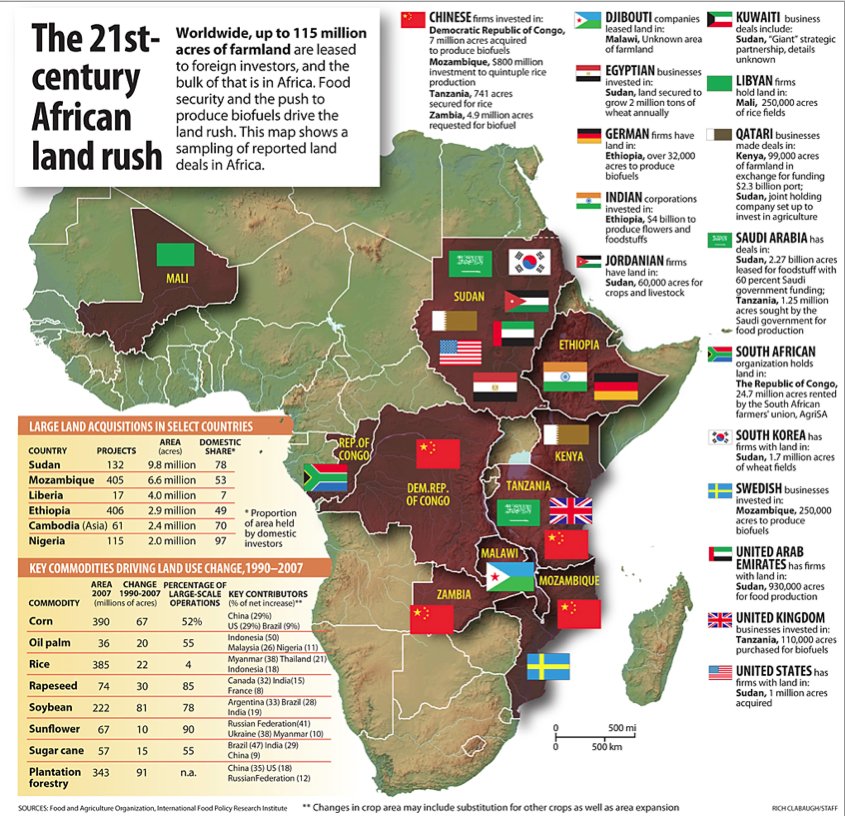

As fears about food security slowly move into focus in the international community, much of East Africa is being divvied up once again for its fertile land; even the head of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, Jacques Diouf, is calling some projects “neocolonialist”.[2] The new phenomena of land grabs in East Africa by private investors and state-led initiatives begs immediate attention. Although there is a movement within the international political economy to support this trend, land grabs pose a real threat and has the potential to lead to grave human and environmental degradation. Land grabs compromise the autonomy of East Africans, especially women, to make a living and to provide food for themselves and their families.

Agribusiness has largely snubbed its’ nose to those at the very bottom of the food production chain. This is problematic for numerous reasons, mostly because it affects millions of people. In Kenya alone, 75% of the population lives in rural areas.[3] They are possibly subject to these land grabs and have little autonomy over the fate of their livelihoods that are already extremely sensitive to market fluctuations in the price of raw goods. This vulnerability is especially true for women, as 90% of rural women in Kenya work in the agricultural sector.[4] Kenya isn’t the only East African country where the overwhelming majority of rural women work in the agricultural field. It is estimated approximately 60-80% of all food grown in Africa is produced by women.[5] Land tenure deals have a direct effect on the lives of rural women by stripping them of their source of income, an incredibly harmful and dangerous fate for such a vulnerable population. This is because rural East African female farmers are born into overwhelmingly patriarchal societies that govern their labor, their access to land within the context of customary land rights, and are therefore further disadvantaged by liberalization and market-based reforms.

The nature of rural East African women working in the agricultural sector is severely limited by the constraints of their gender in a patriarchal society. There are wider customary laws and norms that women are always subjected to, such as issues of labour, health, and childcare. Stewart writes “…agricultural labour is guided by wider community norms which embody assumptions about gender roles.”[6] The value placed on women’s labour is significantly lower than their male counterparts, dictated by specific gendered work that is in the realm of their familial responsibilities. Though advocates for African women’s rights push for tighter labour laws and fair wages, author Ann Stewart explains: “Much of the agricultural work undertaken by women is ‘informal,’ unregulated by contracts of employment or labour laws because women often labour as family members, rather than owners on farms.”[7] This poses a roadblock for those women wishing to get fair compensation from land tenure deals. If women who farm don’t own their own labour or are severely underpaid, it is reasonable to conclude that if compensation was given to African residents, their husbands or fathers would be the one’s benefiting from it. This would further strengthen their financial control over their wives and daughters.

Liberalization schemes and market based reforms rarely benefit small famers, especially rural women. This is due to their inability to compete in such a cut-throat, tumultuous market. Author Ann Stewart explains that women are particularly hurt by liberalization, as it leads to a roll back of state services such as health care and education—issues that directly affect women.[8] She adds that liberalization schemes also lead to reduced tariffs, which lead to a smaller tax base, leaving governments with little spending money on social services.[9] With less money spent on social services, women have little option but to demand more from themselves and their female children. These issues are further exacerbated when one considers that “the risks within market-oriented strategies include economic marginalization and loss of land…”[10]Land tenure deals understandably place an incredible amount of stress on small farmers, however, in the world of privatization, new land market opportunities have tended to disadvantage women, as men find it easier to appeal to this new emphasis on investing.[11] With less money, less opportunity, and fewer social services, East African women have historically turned toward their extended family for support. But as more pressure is placed on the value of land, society grows more individualized, and the economy more privatized, notions of reciprocity and social safety nets of extended families are breaking down, further disadvantaging women.[12] Already in a vulnerable position, liberalization and privatization schemes place great stress on rural female farmers, as they simply have very few resources to support themselves and their children.

[1] Oxfam Canada. (2011, Fall). Oxfam responds to food crisis in East Africa. Oxfam Canada News,p.1,6.

[2] “Buying farmland abroad,” 2009, para. 26

[3] Stewart, 2010, p. 26

[4] Stewart, 2010, p. 32

[5] Englert & Daley, 2008

[6] Stewart, p. 31

[7] Stewart, p. 31

[8] Stewart, p. 32

[9] Stewart, p. 32

[10] Jacobs, p. 181

[11] Englert & Daley, 2008

[12] Englert & Daley, 2008

One of the reasons why land tenure deals pose a real threat to East Africans is that it removes them from their position as farmers in the agricultural production chain. In her book “The Challenge for Africa”, Kenyan activist and Member of Parliament Wangari Maathai writes:

“Our food might be produced in Kenya— either chickens or rice, as well as some greens— but the income received from it generally flows in one direction: out. Consequently, the money brought to rural areas through the sale of commodities such as cash crops is then siphoned back to the town where the consumer goods are transported from, and eventually repatriated to the countries that produce them.” [1]

Replaced by foreign farmers, land grabs force East Africans to be removed from the circle of economic activity, and all the money and food produced from the harvest goes directly to the purchasing countries without a penny distributed to small farmers.

The system of agricultural production already financially benefits those at the top rather than the bottom. Stewart explains: “By placing a premium on product development, value chain coordination and marketing, the system delivers the bulk of the gain to those involved in marketing and retailing, rather than growing crops.”[2] If international corporations like Monsanto are already making a large return on agricultural production, why must they insist on completely removing East Africans from the picture? The work of smallholder farmers isn’t lucrative—it is barely enough to survive on. To insist on their removal is undeniably inhumane. But as is the case with all other privatization schemes, to try and compete alongside these companies is more than financially difficult— it’s nearly impossible. Stewart states:

“Those who continue to pursue a livelihood in local markets must contend with the shadows of global markets, often finding themselves disadvantaged by changes associated with market development.”[3] Furthermore, due to their gender obligations and restrictions, female smallholder famers simply do not have the financial means to complete any post-harvest activities, such as large scale sorting, packaging and refrigeration.[4] Unable to compete in the shadow of global agribusiness giants, female farmers are left to find other methods of supporting themselves and their families.

Further exacerbating the many problems involved with land grabs is the issue of customary land ownership. In an effort by governments and the World Bank to formalize land ownership in much of East Africa, land titles were granted to those who registered their family’s land. Stewart accurately explains in detail the problematic tendencies with customary land ownership:

“Land is subject not only to the state law system but also to the customary land tenure systems of its [Kenya’s] 42 ethnic communities. Under the long-running Kenya formalization process, owners of customary titles are a free simple estate in the land, which can then be used and disposed of with minimal restrictions.”[5]

Unable to claim land as their own, governments are free to dispose communities that have been residing on pieces of land for hundreds of years without much trouble. Stewart writes, “customary rights of use are not recognized under the Registered Land Act, and so are not included as overriding interests.”[6] Land titles however are only granted to males, women’s access to land is only through marriage, divorce or inheritance. Unable to access markets, command their labour, or own land women are utterly left helpless—dependent on their husbands. In Kenya, it is estimated that women own 1% of registered private land, 5-6% hold land in joint names.[7] Women’s lack of opportunity to secure land rights under vastly patriarchal societies make them incredibly vulnerable to land grabs for several reasons; they are unable to receive compensation for land they predominately work on, and they have no negotiating power in community discussions regarding the customary uses of land, and their relocation.[8] Any attempts to remedy women’s lack of access to land has been futile since formal land titles are the only thing that are recognized. Women are thus ignored by any state lead initiatives[9] However, the situation isn’t entirely bleak, Englert and Daley explain: “…tenure reforms can be shaped and influenced by those who are concerned to protect women’s land rights.”[10] Because host East African countries are almost jumping at the opportunity to create land tenure deals, lobbyists, advocates, and even those countries buying or those investing in the land, have the unique opportunity to address gender inequality. Englert and Daley write, “it requires that gender be addressed seriously and integrally in all land policy, administration and reform initiatives.”[11] This could have a huge impact on rural East African female smallholder famers. Though exact figures aren’t yet available for the number of people displaced by land tenure deals, it can be assumed it is close to tens of thousands of people worldwide.

As the rate of successful land grabs continue to grow, it is morally imperative that a code of ethical conduct for foreign countries or businesses be adopted in order to eradicate further violation of human rights. This seems like a viable solution, as purchasing countries are the ones courting host countries, therefore host countries can set forth their agenda and expectations. As female rural smallholder farmers are already disadvantaged by liberalization schemes and patriarchal East African society, a preferential hire agreement of locals, particularly women who have previously worked their land would promote economic independence and provide new opportunities for them, such as learning new technological skills on new machinery. There would of course have to be a handsome compensation for those thrown off their land and environmental regulations clearly outlined and put into effect. Stewart writes: “The inclusion on a ‘social clause’ requiring all members [of the WTO] to enforce minimum labour standards was opposed by the majority of states, particularly in the developing world, and business lobbies.”[12] But because host countries are the ones being courted, they have the unique opportunity to conduct business that serves the purpose of ultimately bettering their citizens financially and socially. There is the potential for the fate of small-scale rural female farmers to continue making a living for themselves and their families on their farms, Jacobs states “…these examples indicate that positive outcomes for women within land reforms require democracy, transparency, and commitment to gender equity.”[13] It requires a commitment to change by policy makers, lobbyists, foreign countries and agribusinesses. To correct this prevailing bottom line ethos, they must favor a more just and principled dedication to sustaining the livelihoods of those, who thousands of kilometers away produce our dinner.

Works Cited

Englert, B., Daley, E. (Eds.). (2008). Women’s land rights and privatization in Eastern Africa. Woodbridge: James Currey.

Jacobs, S. (2010). Gender and Agrarian Reform. New York: Routledge

Maathai, W. (2009). The challenge for Africa. New York: Pantheon Books

Peterson, L. E., & Garland, R. (2010). Bilateral investment and land reform in Southern Africa. Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com.ezproxy.library.dal.ca/lib/dal/docDetail.action?docID=10406256

Stewart, A. (2010). Engendering responsibility in global markets: valuing the women of Kenya’s agricultural sector. In A. Perry-Kassaris (Ed.), Law in pursuit of Development (pp. 26-40). New York: Routledge

Buying farmland abroad: Outsourcing’s third wave (2009, May 21) The Economist. Retrieved from http://economist.com/node/13692889

Did You Know?

Approximately 60-80% of all food grown in Africa is produced by women (Englert & Daley, 2008).

90% of rural women in Kenya work in the agricultural sector

(Stewart, 2010, p. 32).

In Kenya, it is estimated that women own 1% of registered private land, 5-6% hold land in joint names

(Stewart, 2010, p. 34)

Get Your Hands Off Our Land

By Arielle Cohen

Magazine Posts

Magazine Posts Table of Contents

Table of Contents