arielle's post

arielle's post

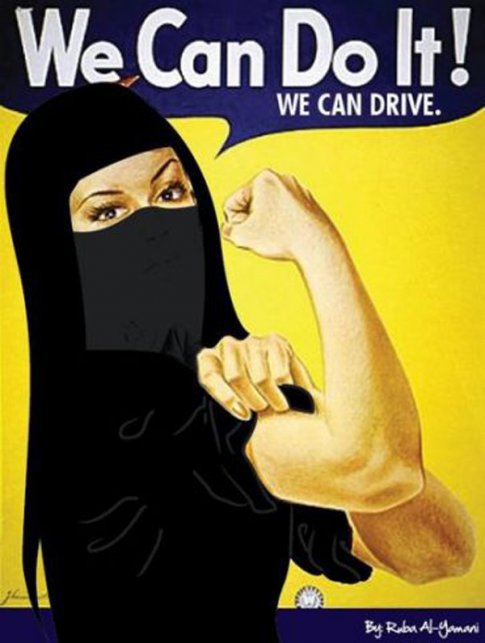

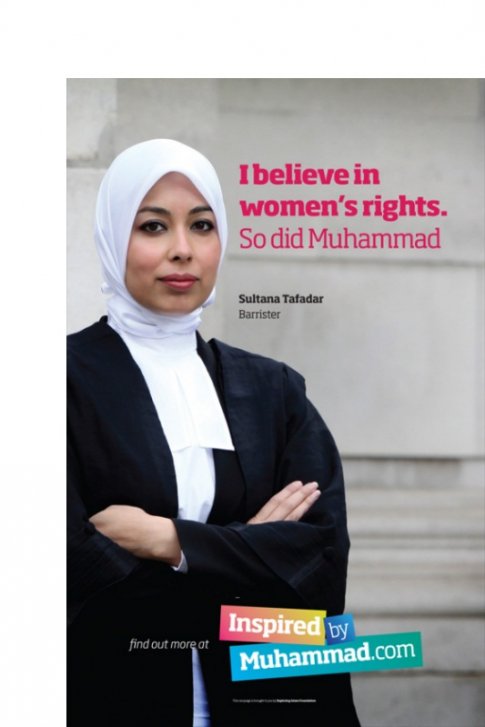

Damn the Man!

Damn the Man!

Alec's Post

The Long Road to Reform

By Alec Cumming

Arrival in Riyadh International Airport, and the first steps taken in Saudi Arabia, has a distinct feeling of significance for a western traveler. Immediately one is faced with the drastic cultural differences present, perhaps the most obvious of all can be found in the presence of Saudi women. Or rather, a lack of presence. There are no female airport workers, or indeed female workers of any sort to be seen upon arrival. The only women in sight are covered head to toe, wearing the niqab and the abaya to cover their entire bodies, and move like shadows behind their male escorts.

As a male traveller, I was spared the enforcement of a dress code, since there is none for men. But all women, no matter their descent or religious beliefs are required by law to wear the niqab, to cover the head and face, and abaya, to cover the body to the toes, at all times in public. Compliance with the law is ensured by the Mutaween, or religious police, who operate almost entirely unrestricted in their enforcement of the official policies of the Kingdom[i]. Punishment for any infractions are often swift and brutal in nature, with the accused having no access to a lawyer, and no semblance of a fair trial before being subjected to the will of the Mutaween, be it torture, flogging, maiming or beheading[ii]. Even small infractions of the dress code can result in public beatings or arrest, keeping women well in check.

conditioned to expect male dominance and female subordination at all times, something which is not easily undone.

The level of institutional discrimination against women in Saudi Arabia is unrivaled. The laws in place are unmatched in their blatant disregard for the notion of female mobility, and the method of law enforcement is barbaric at best. However, the recent decision to allow women to vote and run in elections is an extremely promising development, and the actions of Saudi reforms like Rania Al-Baz and Nadia Bakhurji are creating important discussion around traditionally taboo topics. There are sign of change. The challenges however, years of male domination that have created an ingrained expectation of complete authority over women, will not be overcome quickly or easily. Indeed, a substantial shift in cultural values is required for women to approach any sort of equality, something that will likely be fraught with backlashes and violence, and thus cannot and should not be rushed. The events in the lead up to the 2015 elections will be extremely telling in terms of male acceptance of the idea female voters, and the results of the election, should it go smoothly, could be the start of a more profound and widespread change in the Saudi mindset.

[i] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[ii] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[iii] Doumato, E. A. (2003). Education in saudi arabia: Gender, jobs, and the price of religion. In E. Doumato & M. Posusney (Eds.), Women and Globalization in the Arab Middle East (pp. 239-257). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

[iv] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[v] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[vi] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[vii] Silvey, R. (2008). Transnational domestication. In C. Elliott (Ed.), Global Empowerment of Women (pp. 101-117). New York, NY: Routledge

[viii] Variety Arabia Staff. (2009, March 06). Saudis open screen door. Variety,

[ix] Buchanan, E. (2011, September 25). Women in saudi arabia to vote and run in elections. BBC

[x] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[xi] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[xii] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

[xiii] Lichter, I. (2009). Muslim women reformers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Saudi laws regarding women are entirely religious ones, overseen and interpreted by religious scholars under the oversight of the King, who maintains an absolute, and undemocratic authority. Under these laws, women are heavily restricted in nearly every way imaginable; banned from driving, traveling alone, or even checking into a hospital without written permission from a man[iii]. Marriage laws allow for men to easily obtain divorces, while women must request a court approval, where a woman’s testimony is treated as presumption, rather than fact[iv]. Indeed there are a variety of forms that marriage in Saudi Arabia can take, including temporary marriages, marriages that require no financial support from the husband to the wife, and marriages that allow for older men to marry significantly younger women, or even girls. There are even accounts of 3 three old girls being married off by their fathers, with the marriage being consummated by the age of 9[v].

There are somewhat more encouraging trends to be found in the Saudi education system, where women make up 58 percent of university students, although they are restricted from studying certain subjects that are considered ‘male’, like engineering. These high university enrollment numbers are somewhat of an oddity however, since women make up a lowly 5 percent of the workforce in Saudi Arabia, and an estimated 33 percent of Saudi women are believed to be illiterate[vi], thus showing not only that this university education is rarely put into practice, but that a vast number of women are still denied even basic education. In a similar case, while there are now a handful of high profile women working high ranking positions in the Saudi government, it is only through their privileged backgrounds and a wealth of connections that they have risen to positions of power, while the vast majority of women in the country have no power at all.

Recent improvements for women include a change to be recognized by name on government identity cards in 2001, rather than the property of a male[vii]. In 2008, women were giving the right to check into hotels on their own, and this year, for the first public screening of a movie in 30 years, it was deemed acceptable for women to watch the movie in the presence of men[viii], but the most significant change was the announcement that women would be allowed to vote and run in elections beginning in 2015[ix]. Despite most of these gains being meager and long overdue, many traditionalists were, and remain, drastically opposed to even the smallest of these reforms and allowances, showing a complete lack of acceptance for the improved rights of Saudi women. Indeed Saudi Clerics and traditionalists are quick to write off women’s rights as a form of cultural imperialism; the corrupting effect of western culture on the Arab world. Such a stance provides no avenue for discussion on such issues with westerners concerned about the rights of Saudi women, but there are, however, reformers living under these conditions who challenge these conditions on moral and, quite importantly, religious grounds. Believing that the Quran has been misinterpreted to oppress women, this scripture based argument is much harder to ignore than the criticisms of the western world.

One such reformer is Rania Al-Baz, who is perhaps the most high profile advocate for change in Saudi Arabia following her appearance on an episode of Oprah. Al-Baz was nearly beaten to death by her husband in 2004, who left her unconscious outside of a hospital with extensive injuries received from repeatedly smashing her head against the floor of their home[x]. As a well-known news broadcaster, Al-Baz was in a position to make a stand against this type of abuse which is all too commonly ignored in Saudi Arabia. Al-Baz became the first Saudi Woman to press charges on her husband for abuse, and in large part due to the media attention paid to the story, Al-Baz won the case, but pardoned her husband in exchange for a divorce and child custody. This was a tremendous victory for the recognition of women’s rights in Saudi Arabia, but Al-Baz’s actions following her victory, in particular her appearance on Oprah where she was seen with an unveiled face, tainted the victory. Her unveiled face was as far as the thought process went for many Saudis; she invited the violence from her husband through her inappropriate behaviour[xi]. Al-Baz’s case provides one of only examples in Saudi Arabia where a women was able to effectively use the existing power structure in her favour, to protect herself from an abusive husband, but once she stepped outside the rigid gender role set for women, the impact of the decision was easily deflected by the cultural demands of Saudi men.

Nadia Bakhurji is another prominent female Saudi reformer, who attempted to run for political office in 2005 using a legal loophole, but was denied the chance to run by the Saudi government, citing logistical issues[xii]. Bakhurji believes that the issue is a cultural one at the core, rather than a religious one, explaining that “it is not in our culture to tolerate. We are very judgemental. This is wrong. We need to educate people to be tolerant rather than judgemental… this kind of narrow-mindedness which is programmed… socially from an early age needs to be changed. The only way we can move forward is to get rid of this ignorance”[xiii]. Indeed, while the legal changes have been slow to come, there does seem to be some willingness to consider change at the top. The real resistance to change comes from the male population at large, who has been

The Rising Rights Movement in Saudi Arabia

Did You Know?

-58% of university students in Saudi Arabia are women

-The first elections allowing female participation will be held in 2015

-Women constitute only 5% of the workforce

Magazine Posts

Magazine Posts Table of Contents

Table of Contents